glass flowers

There is a certain strength to fragility. After introduction to Harvard Museum of Natural History’s featured exhibit, "Glass Flowers", I am reminded how strength, as it applies to physical boundaries, is worth exploring and preserving. There is utility in something of such fragile form. The motive for such meticulous workings also calls question: What must the mind be like for those whose craft truly stands aside, if not above, the rest?

The "Glass Flowers" were a commission conceived by Harvard Professor George Lincoln of the Botanical Museum in 1887. The workings are from Father and Son, Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka. Their master glass craft handed through generations and all of their work was melted and manipulated over their wooden desk near Dresden, Germany. But there’s a reason that these men were on the map, especially to a professor overseas. The wonder Leopold had for life brought him to a place where he could work with his hands and embed heart into his creation. There’s a beautiful quote that speaks of his intrigue for marine life during a period he was physically dormant due to illness:

“It is a beautiful night in May. Hopeful, we look out over the darkness of the sea, which is as smooth as a mirror; there emerges all around in various places a flash-like bundle of light beams, as if it is surrounded by thousands of sparks, that form true bundles of fire and of other bright lighting spots, and the seemingly mirrored stars. There emerges close before us a small spot in a sharp greenish light, which becomes ever larger and larger and finally becomes a bright shining sun-like figure.”

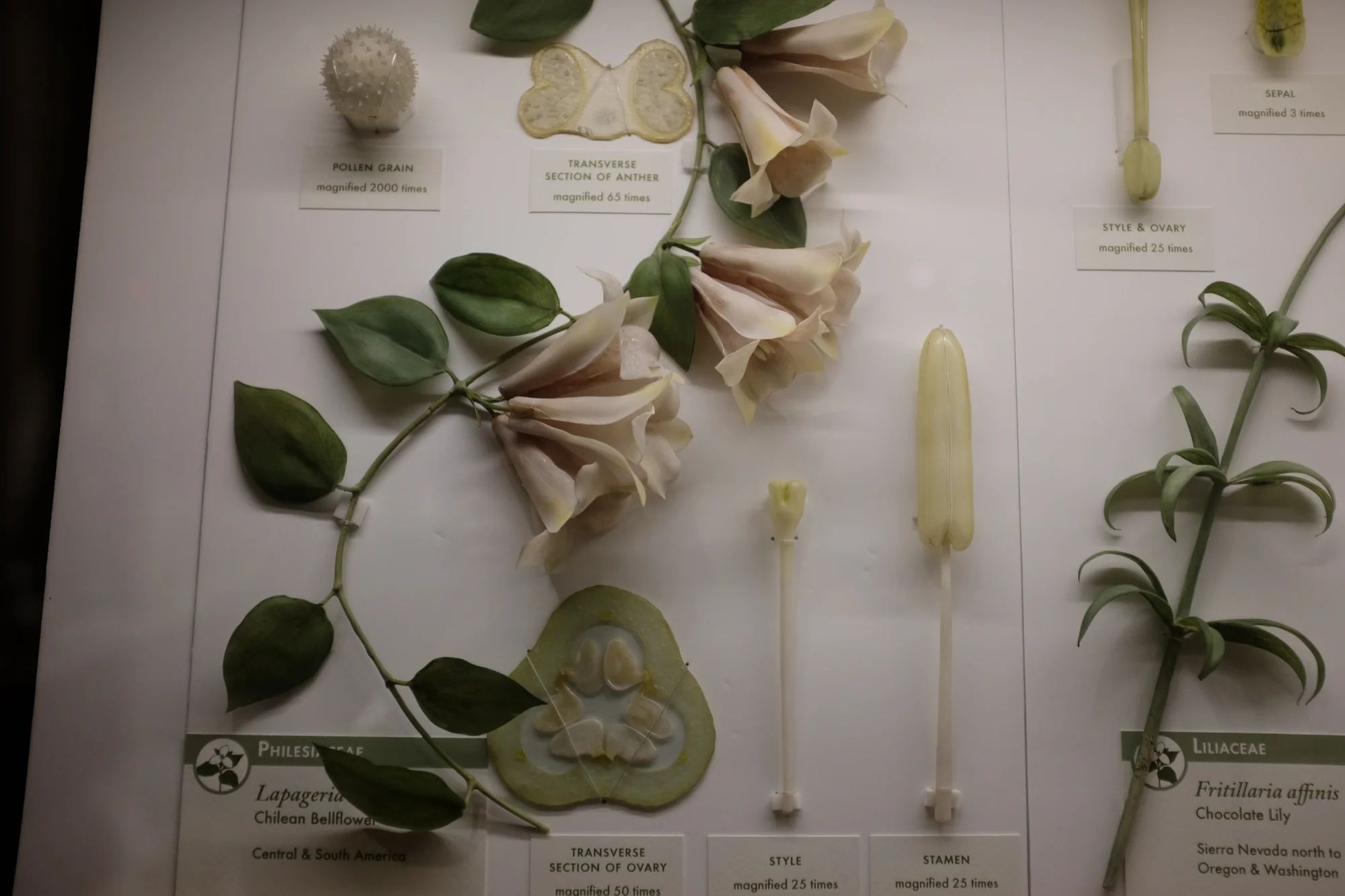

It was this marvel at marine creatures that would inspire his first foray into glass biology that eventually lent itself to work with glass botanicals. This level of detail birthed in wonder, is obviously apparent in such intricate, delicate designs, and tenacity to produce such quantity. There is heart, in that work, continued inspiration for life. And vast this “Glass Flowers” project was, with over 847 individual pieces, these specimens range from a magnified peek of the inner organs of flowers-- pistils and stamens-- to true-to-size petal and stems.

With all its wonder born creation, this art could not have been without support. Not strictly for aesthetic, there was application of science. What the professors and patrons saw in the benefit of giving a third dimensional take on the typical plate pressings of tradition teaching, helped onlooker better understand anatomy and scientists further their studies. A direct example of this was the model spores for certain species of apple that were able to be introduced and understood so that the actual fungi could be contained and controlled. A brilliant attribute of art contributing to science.

Seemingly redundant, this glass behind glass has stood the test of time. As with much art, these pieces have outlived their creators, now settling into 120 years of age. They have aged well and in assisted fashion-- the museum goes to meticulous lengths in preservation as conditions ranging from temperature, humidity, handling, and light exposure all contribute to the degradation of the pieces.

“Many people think that we have some secret apparatus...but it is not so. We have tact. My son Rudolf has more than I have, because he is my son, and tact increases in every generation...and it is your own fault if you do not succeed. But, if you do not have such ancestors, it is not your fault.”

If I could wrap my arms around something aside visual splendor (especially as it applies to this exhibit) it’s drive. It’s wonder. It’s style. There is something you have that no one else does. No matter your craft or service, you might be handed the branded tools, but the application is your own. That idea, that art, needs to be continually acknowledged and supported, because there is strength in it, there is enrichment, there is evolution.

Glass Flowers is currently on exhibition at the Harvard Museum of Natural History in Cambridge, Ma.